“Because it’s there.”

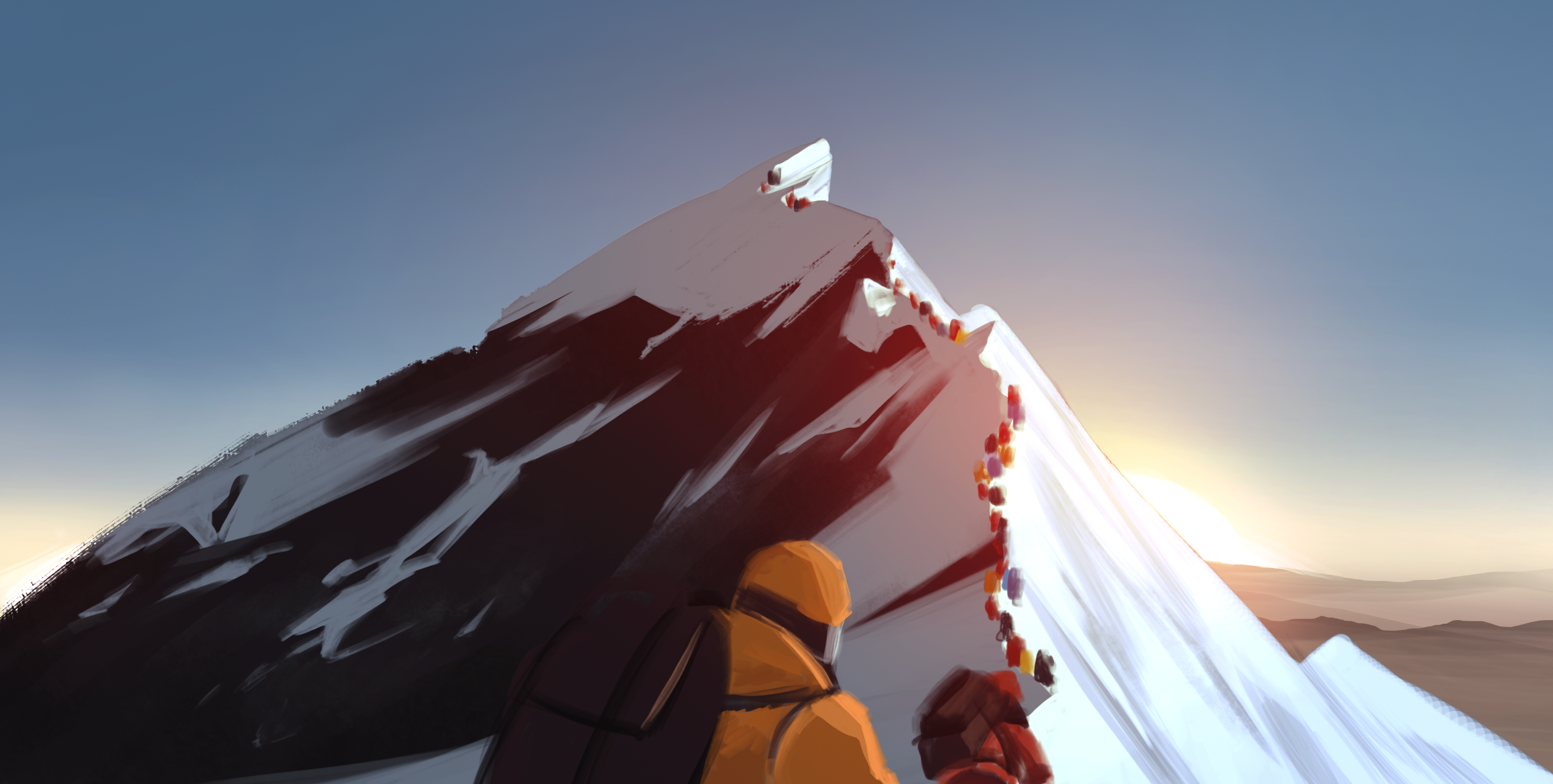

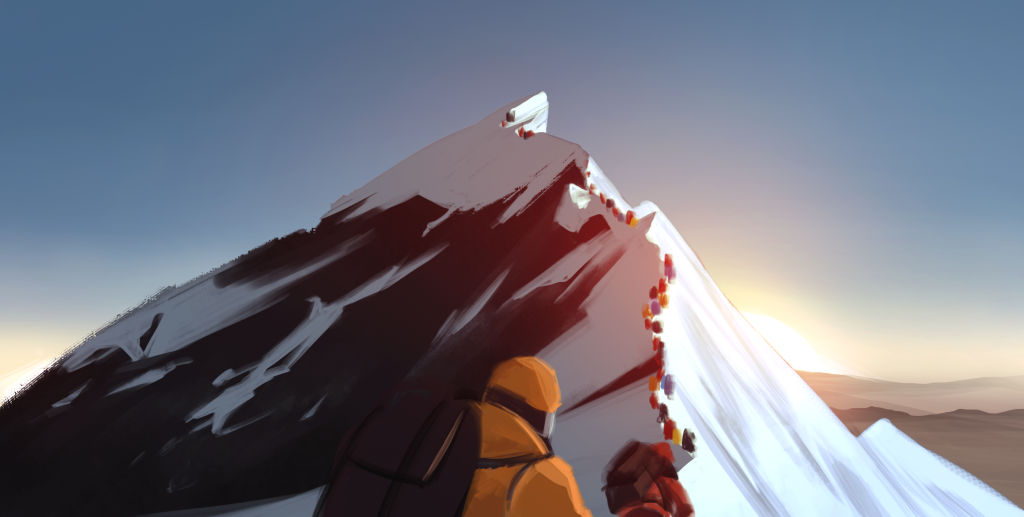

While on a publicity tour in advance of his doomed 1924 expedition to climb Mount Everest, George Mallory was asked over and over and over again: “Why climb the highest mountain in the world?” His pithy response was probably born of frustration with the media, but it’s entered into the culture of mountaineering, climbing, and endurance sports at large as a catch-all phrase. It’s a motto, a statement of purpose, a self-contained ethos, and the ultimate motivation for embracing the impossible. More than likely, it was the same spirit that drew hundreds of climbers — some dangerously inexperienced — to Everest on Wednesday, May 22nd, 2019, the day that Nirmal Purja took his now-famous photo of a technicolor down-suit traffic jam on Everest’s Hillary Step in a prelude of one of the deadliest days in the mountain’s history.

For anyone remotely interested in the outdoors or adventure — or anyone with any degree of ambition, honestly — Everest has a kind of sacred presence in the mind. For much of its history, though, climbing Everest was a dangerous, often deadly prospect. Mallory and his climbing partner, Andrew “Sandy” Irvine died during their attempt on the mountain. Their remains weren’t located until 1999 — 75 years after the beginning of their doomed expedition — and it remains one of the greatest mysteries of mountaineering whether they actually made it to the summit. However, modern clothing and gear technology has significantly decreased the risks involved with climbing the mountain. High-tech down suits, fixed ropes, assisted belaying devices, and much more have improved alpine safety in leaps and bounds — and yet climbing Everest has never been more dangerous, more deadly, or less sacred. Far from being the peak of adventure and oneness with nature, climbing Mount Everest has become a booming industry for the moderately fit and immensely wealthy. From the permitting process to the exploitation of Sherpa labor to the dangerous consequences of inexperienced climbers and cut-rate expeditions, the state of Everest today betrays the spirit of mountaineering and turns the almost-sacred marvel of nature into a deadly playground for climbing’s one percent.

An Expensive Enterprise

At first glance, it might be surprising that overcrowding and inexperience are rampant issues on Everest; one of the most commonly known facts about climbing the mountain is the staggering cost. Though there are about 20 named routes to the summit of Everest, the two that most climbers use are the South Couloir route starting in Nepal or the Northwest Ridge route starting in Chinese Tibet. Regardless of which route you use, however, you have to get a government-issued permit from whoever manages the route you’re using. In Nepal, getting a permit to summit Everest costs $11,000. This amount on its own would be enough to raise an eyebrow, but it’s an even more staggering sum when one considers the fact that paying this fee only grants an individual permission to climb the mountain — this cost fails to cover transportation, expedition and guiding fees, and gear costs, all of which can add thousands more onto the already exorbitantly high amount of money. For the truly talented and experienced mountaineer, some of these won’t be an issue: gear as well as many travel fees can be provided by sponsors, and professional climbers often avoid climbing with commercial expeditions. For the average climber, though, these expenses can be a huge deterrent to climbing Everest and may cause them to rule out the possibility of even trying.

So what exactly is the problem with that? It may seem as though this is a net benefit— climbers who aren’t experienced or skilled enough to get sponsors are being kept away from the mountain by the expense. In principle, this system works, but there are always those who can pay. Every year, people with money to spend — some climbers, some not — apply for permits in Nepal and China, all with differing levels of experience. That experience level, though, matters less than one might think. Because Everest permits are a steady source of state income for both China and Nepal, it is in the countries’ best interest to give out as many as they can. As a result, skill checks are few and far between, which leaves the mountain open to climbers of many skill levels, including those inexperienced to the point of putting themselves in danger.

“How hard could it be?”

Mountains are dangerous. Since the first attempts on Everst in the early 1900s, thousands of people have been injured and over 300 people have died while trying to reach the summit. The causes vary:. The thing about all of these hazards, though, is that they are largely preventable with experience. That being said, many Everest climbers lack the necessary experience. Both permitting governments and many expedition companies perform few to no skill checks.

In recent years, it’s become a common practice for expeditions on Everest to give their team members some of their first instruction in mountaineering upon their arrival at base camp. When done correctly, this instruction can be sufficient and has gotten plenty of eager climbers to the summit and back safely. That being said, the more experience you have with your equipment, the more likely it is to help you when you really need it. Thankfully, many reputable expedition companies such as Alpine Ascents International have such requirements in place for their hopeful team members. Not shockingly, these companies have some of the safest and best summitting rates in the business. Some companies, however, are more than willing to compromise safety for a little extra cash, risking the lives of both their team members and other climbers in the process.

The Traffic-Jam Special

In Purja’s famous traffic-jam photo, hundreds of climbers were stuck in one massive line on a fixed rope leading up the Hillary Step, one of the most difficult and dangerous portions of the climb. Aside from being a commentary on the commercialization of climbing Mount Everest, Purja’s image demonstrates another real danger posed by the sudden influx of people climbing Everest: overcrowding.

Perhaps the most dangerous obstacle when climbing Everest isn’t a specific part of the route or acquiring a certain skill, but a spectre that looms over every part of an expedition: uncertainty. The Himalaya are dangerously finicky; the safest window for climbing the mountain usually comes down to a few days in late May. Climbers will sit in base camp for weeks waiting for the weather reports to come in and for the window to be announced. And when the window comes, hundreds of climbers begin a race towards what is known as the “death zone.”

At an altitude of around 8000 meters, the atmosphere becomes so thin and devoid of oxygen that any human spending any protracted amount of time above that altitude faces certain death. This is the death zone, the most painful, difficult, and dangerous parts of any Everest climb. . Without well-planned use of supplemental oxygen, climbers face unimaginably painful deaths as they suffocate at the top of the world. Even with supplemental oxygen, though, the death zone is dangerous, especially if you’re caught there much, much longer than planned.

A December 2019 article by GQ gives some of the details of what happened after Purja took his photo. One of the big hazards that day came in the form of one woman on the Northwest Ridge route of Everest, who caused a multi-hour traffic jam (completely separate from the one Purja captured on film!) and several deaths, all because she was too scared to go down a ladder. This whole debacle was compounded by a storm that rolled in as night fell, making conditions in the death zone even more devastating than usual.

Traffic jams, though, are just one of the many problems caused by overcrowding. When most climbers attempt Everest, they use fixed ropes, ice screws, and other gear that has been placed along the route by Sherpas and other professional climbers to ensure their safety. With low amounts of people, this gear is perfectly reliable, but during a traffic jam, one person falling could set off a chain reaction that overloads the gear and tears it out of the mountain, dragging potentially dozens of climbers into a catastrophic fall.

Clearly, crowds and inexperienced climbers pose huge dangers to themselves and others, in large part due to the economic machine that allows them onto the mountain. Some of the greatest victims of Everest’s oppressive economics, though, are not the climbers themselves, but the people who work day and night to make sure they make it to the summit: the Sherpas.

The Icefall Doctors

The Sherpa people have been part of Everest’s history since before Westerners even began to think about its conquest. The Sherpa people have lived in the area of Everest since the 12th-13th centuries, and Tenzing Norgay teamed up with Sir Edmund Hillary to be the first to summit the mountain in 1953. These days, Sherpas are a ubiquitous part of climbing Mount Everest, though many don’t realize or appreciate just how much work and risk they take on to create the Everest experience for summit hopefuls. Weeks before climbers even arrive at base camp, a team of highly skilled Sherpas known as the Icefall Doctors venture out into the Khumbu Icefall, one of the most dangerous parts of the climb, to determine the route, set up ladder bridges and fixed ropes, and prepare the Icefall so that climbers can find safe passage through to Camp One. Icefall Doctoring aside, Sherpas set fixed ropes and camps for the entire Everest route well in advance, manicuring the route to the top to make it as comfortable and safe for summit hopefuls as possible. Even once climbers arrive, the Sherpas’ work still isn’t done. Many Sherpas work as guides and porters, leading intrepid climbers through the route to the top while carrying stupendous loads for their clients and often using minimal technical gear.

This work is incredibly risky — since Sherpas started working on the mountain, they’ve comprised nearly a third of all deaths (around 94 Sherpas) including a notorious disaster in 2014 when an enormous ice feature collapsed onto the Khumbu Icefall, killing 16 Sherpa guides and no Westerners. So why do Sherpas do it? For many, it’s an economic no-brainer. In Nepal, the average monthly income is around $50 in American money. In about the same amount of time working on Everest, a guide or an Icefall Doctor can make anywhere from $2000 to $5000. If you can work with an expedition that provides life and accident insurance, even better, but at that kind of rate, you take whatever work is available. In the wake of the 2014 disaster, Sherpas threatened to go on strike, and the Nepali government significantly compensated the families of the victims, but formal protections have a long way to go.

Because It’s There.

The reality is that most of the people reading this article (myself included) are not going to climb Mount Everest for one reason or another. The state of Everest, though, is a cautionary tale in the commoditization of the natural world. As a society, we tend to take an access-centric approach to conservation. To ensure that a natural space is preserved, we make it as enticing as possible and as easy to access as possible. Another example that’s a little closer to home is Prairie Creek Park, just down the road from UTD. A few months ago, a gravel path through a small wooded area was replaced in part by a sidewalk. It increased how often people went came to the park and made it a visibly more common destination in Richardson. For me, though, it took away some small element of the sacred from one of the few natural spaces I could really count on being able to escape to.

In all honesty, the way I felt about that sidewalk is emblematic of the problem I’m trying to get at: natural spaces often only have what value we can get out of them, rather than intrinsic value as part of our planet. This, I think, is much of the problem that faces Mount Everest: what for a long time was a sacred place touched only by low-impact, highly professional expeditions. Today, Everest has become a commodity, and a dangerous one at that, putting lives at risk year after year in a never-ending quest to make the mountain more accessible. I don’t have an easy solution to that problem, or to the wider problem of how we view nature in terms of ourselves — that’s far too wide-reaching an issue to fix in four pages, though. I can only hope that as a society, we can begin to move away from the need to own nature, both in our hometowns and across the world, and to simply appreciate the magnificent and the sacred because it’s there.

Christian Kondor (junior | mathematics)

Christian is AMP’s web editor and elusive political correspondent. He has no idea what he’s doing and you can’t stop him.

Comments