“America is back,” President Biden proudly declared to the Munich Security Conference, an annual meeting on Western defense policy, on February 19th.

Six days later, his administration dropped seven 500-pound bombs on a small building complex in eastern Syria. Congress wasn’t notified of these strikes until over 48 hours after they had been launched. The United Nations were not notified except in a short letter of justification. Members of the Senate were never briefed.

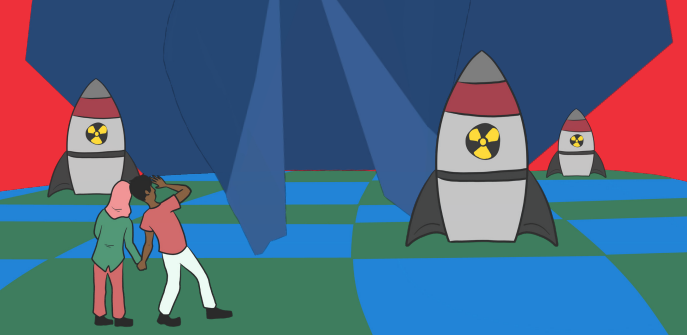

Biden didn’t lie. America is back, indeed. The airstrike is the truest manifestation of U.S. hegemony, embodying the now nearly unchecked power of the American executive to condemn random individuals thousands of miles away to death at a whim. For the people of the countries brutalized by this murder, it is the true face of America. We forget, after all, that those victimized by our overseas adventurism are themselves people.

In Pakistan, a 12-year-old boy named Zubair was taught to fear blue skies. Unmanned drones, operated by 20-year-olds in Virginia, cut across the skies when they are blue. Yemeni weddings are subject to sudden, seemingly random violence, perpetrated by the armed forces of the state that claims to represent us. Korea and Vietnam, two nations subject to U.S. intervention over a half century ago, are still recovering from America’s wanton destruction of every aspect of their respective societies.

These are the true effects of America’s foreign policy. These are the true effects of bloated military budgets, imperialism, the military-industrial complex, and a global strategy that refuses to recognize the basic humanity of people who happen to be foreign.

In the years preceding the First World War, the British Empire maintained a two-power defense standard. Under the terms of this policy, the British Royal Navy was to be larger than the next two largest global navies combined. On the eve of one of the bloodiest conflicts the world has ever experienced, this was seen as sufficient for an imperial enterprise that ruled over a quarter of the world’s population.

The year is now 2021, and British imperial hegemony has been replaced by another – the American imperial hegemony, wrought not by direct colonial administration, but the imposition of neocolonialism through puppet leaders, unequal trade, and the judicious application of violence. For this new empire, it isn’t enough for the navy to just be larger than the next two largest ones combined.

The budget of the entire United States military exceeds not the budgets of the second and third largest militaries combined, but the budgets of the largest ten combined. Six of these ten – South Korea, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Saudi Arabia – are the U.S.’s close allies. This budget amounts to $934 billion – nearly a trillion dollars, and an unfathomable amount in its own right.

Comparing U.S. military strength to that of its newest political target, China, is revealing. America operates 20 times the nuclear warheads and twice the tonnage of warships. The United States has eleven aircraft carriers—all nuclear-powered; China has two, and neither are nuclear. The United States has over 2,000 fighter jets; China has 600. Washington has 800 military bases overseas; Beijing has three. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the American military constitutes the largest violent force assembled since the Second World War, and the best equipped one in human history.

Yet, somehow, a few dozen Syrians armed with 1990s model Toyota trucks and Cold War-era rifles can present a mortal strategic threat. Somehow, a nation with far smaller military expenditures, far less advanced equipment, and far less reason to go to war constitutes a major defense risk. Somehow, any opposition to the Pentagon’s military dominance is an offense towards the American homeland.

What then, exactly, is the $934 billion in American defense expenditures funding?

Zubair learned to fear blue skies in October of 2012, when he and his younger sister Nabeela were injured in a drone strike in the Pakistani province of North Waziristan. “I no longer love blue skies. In fact, I now prefer grey skies. The drones do not fly when the skies are grey,” he testified before Congress in 2013. Zubair’s story is just a microcosmic instance of the suffering brought forth by American armed forces.

During the Korean War, 20% of the peninsula’s population was killed. U.S. forces dropped 635,000 tons of bombs (including 32,557 tons of napalm) over the course of the conflict. In the Pacific theater of the Second World War, U.S. bombing tonnage only amounted to 500,000 tons. In 1984, future Secretary of State Dean Rusk confessed that the United States bombed “everything that moved in North Korea, every brick standing on top of another”.

During the Vietnam War, 4 million Vietnamese people were killed. U.S. forces dropped over 7 million tons of bombs over the course of the conflict, constituting the largest aerial bombardment campaign in history – even larger than the Allied bombing campaigns of World War Two. Across all of the former Indochina during the conflict in Vietnam, the United States used an average of 142 pounds of explosives per acre.

During the Iraq War, excess casualties range from 150,000 to over a million. The invasion of Iraq created a power vacuum the American government could never hope to fill, and the country exploded into sectarian violence. During the Second Battle of Fallujah, the U.S. military used depleted uranium rounds in a dense urban warzone. More than half of all babies born in Fallujah surveyed between 2007 and 2010 were born with birth defects.

In Libya, NATO intervened against Gaddafi’s socialist government on allegations that his government fired on its own people using aircraft. In a Pentagon defense conference, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates admitted that he “[saw] the press reports but [had] no confirmation of that”. Before the intervention, Libya had the highest Human Development Index in Africa. Now, open-air slave markets are a fixture in Tripoli.

During the ongoing conflict in Yemen, the U.S. has armed and abetted Saudi forces which have unlawfully struck facilities run by unaffiliated aid organizations, declared the entire city of Sa’ada and its population of 50,000 people a valid military target, used white phosphorus munitions on human targets, and targeted medical personnel and the wounded. Nearly 100,000 Yemeni people have died.

No problem has ever been solved by the involvement of U.S. armed force. Even the Second World War, an unquestionably just conflict, was won more through the immense sacrifices of the Soviet Union – which suffered 27 million fatalities – than those of the U.S., which suffered only 400,000. Aside from this one exceptional scenario, the track record of U.S. interventionism has been one of violence, horror, and the wholesale emaciation of entire countries.

These are the costs of U.S. adventurism abroad. They are costs we, as Americans, will never have to pay.

In the West, we are often primed to think of the costs of war in terms of our soldiers, or our timeframes, or our budgets. The needs and the wants of the people who live in the theater of war are made out to be, at best, secondary to the national interest.

This is an extremely cynical assessment of war. A Syrian is a fully-formed individual, with habits, beliefs, customs, interests, families, friends, just as much so as a Yemeni, or a Libyan, or an Iraqi, or a Korean, or an American. Syria itself encompasses a variety of peoples within a certain sociopolitical context that has been brewing for millenia. Political events in these countries are, like all things, intricately contextual, and emerge from a political logic dictated by their domestic situation.

So long as the administration talks about intervention – any intervention, as “minor” as a Predator strike – we need to ask whether it is worth the wounded, the sick, the missing, the refugee camps, the orphaned children, the block-to-block fighting, the basic services collapsing, the evisceration of the national culture, the destruction of thousands of years of human heritage, and, above all, the dead, whose lives were far more important than any Washington policymaker had ever cared to consider.

War – cold or hot – is hell. The next time you see a hawkish pundit urging military action, no matter how minute, no matter where or under what circumstance, consider who will bear the burden.

It will certainly not be you.

Comments