This past July, UT Dallas made national headlines when Computer Science professor Timothy Farage made a tweet calling for a “cure for homosexuality.” Thanks to coverage by the Mercury, response from the student body was immediate, with many claiming that Farage had a history of making such controversial remarks, both in and out of the classroom. The university responded by “unequivocally denounc[ing]” Farage’s remarks and offering students additional options of courses he taught for other professors.

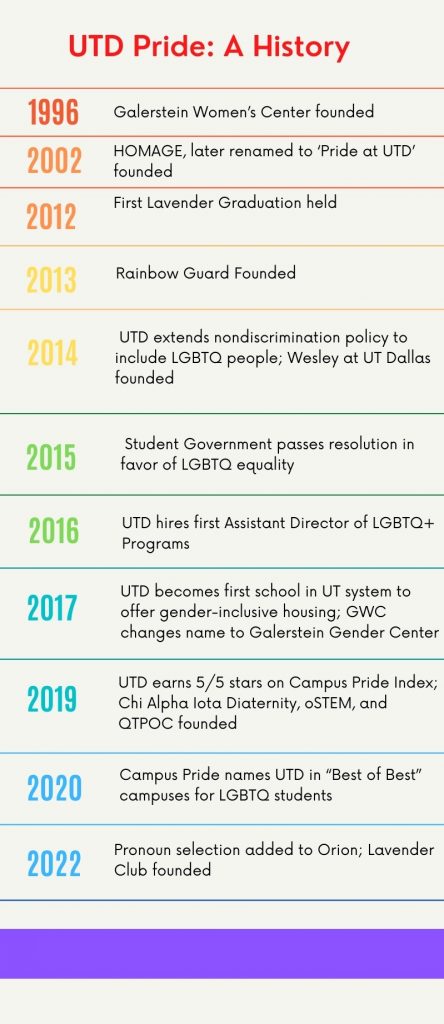

It may come as a surprise that UTD has earned a 5 out of 5-star rating from Campus Pride Index every year since 2019. In fact, only a month before Farage’s tweet, Best Colleges and Campus Pride ranked UTD 14th in the nation among “Best Schools for LGBTQ+ Students in 2022”. On Best College’s website, the video featured on the article is literally about how LGBTQ-friendly UTD’s campus is!

But for most people, UTD’s status as one of the nation’s most LGBTQ-friendly schools in the US is something of a mystery. Many students aren’t even aware of the fact, much less the particulars of how, when, and why it happened.

There are a few reasons UTD is so inclusive of LGBTQ+ students. First, there is UTD’s relative anonymity. As a result of UTD being a relatively young institution (and not having a football team), UTD doesn’t typically receive much media coverage. This means that a lot of policy changes can happen under the radar. Second, there has been a great deal of administrative support of LGBTQ+ students, primarily from the Galerstein Gender Center.

But the driving force behind LGBTQ+ rights at UTD has always been students. In particular, many significant milestones made for LGBTQ+ students in the last decade can be traced to a student advocacy group called Rainbow Guard.

Rainbow Guard was only active for a few years in the mid-2010s, but managed to have a massive impact on the campus. The organization was involved in updating the university nondiscrimination policy to include LGBTQ+ people, establishing gender-inclusive housing, changing the signage on single-stall restrooms, and much more.

Adam Richards, one of Rainbow Guard’s founding members, was able to provide some history of the organization. Richards attended UTD from 2011 to 2019, earning a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering and a Master’s in Political Science. At various points, they served as Treasurer, Vice-President, and President of Rainbow Guard.

“UTD, even in 2011, was already was starting to gain a representation for being queer affirming as a campus,” Richards said.

Rainbow Guard began in 2013 as an off-shoot of Pride, which was founded in the early 2000s as HOMAGE. At the time, UTD already had two administrative groups dedicated towards LGBTQ+ issues: the GGC and the LEAP Committee (LGBTQIA Education, Advocacy and Programming).

However, because Pride was primarily a social club, there was a deficit of LGBTQ+ student advocacy. Richards noted that Pride being socially focused was understandable, since people need safe spaces to escape from politics.

“But we really were not seeing a lot of coordinated advocacy on the student level, even though we had the passions and the minds to do that,” Richards said. So Rainbow Guard was founded by Pride members, with the specific goal of bringing student issues to the administration.

“It was a lot of talking with students about the things on campus that impacted them and the sort of changes they wanted to see, and trying to come up with proposals for the bigger meetings with the Gender Center and other groups,” said Elixah Taylor, policy chair of Rainbow Guard from 2016-2017. Taylor graduated from UTD with a Bachelor’s in Psychology in 2020.

Taylor mentioned that years before Campus Pride Index awarded UTD with 5 out of 5 stars, Rainbow Guard was using their grading system as a reference for advocacy. Campus Pride Index grades schools on factors such as LGBTQ+ safety, housing, and nondiscrimination policy.

“We were trying to set our goals to at the very least meet those standards, if not go beyond them,” he said. In order to meet these goals, Rainbow Guard worked closely with the GGC and the LEAP Committee for several years. UTD being given this distinction in 2019 was the result of a lot of hard work on the part of students and administration.

Of course, bringing student issues to administration is typically the role of Student Government, and Rainbow Guard was aware of this. In fact, Richards was an SG Senator for four years, and was at one point chair of the Graduate and International Affairs Committee. Taylor was not officially involved in SG, but allegedly showed up to so many meetings that several people assumed he was a Senator.

Despite their notoriously low voter turnout rates, SG holds a lot of power as the official voice of the student body. In 2015, SG unanimously passed a resolution in favor of equal rights for LGBTQ+ students — and a year later, UTD’s nondiscrimination policy was updated to include protections based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. Rainbow Guard had been involved in talks on the wording of the nondiscrimination policy, but SG’s support carried a lot of weight. SG was also involved in updating single-occupancy restroom signage to be more inclusive, although Richards noted the project was initiated by Rainbow Guard.

In more recent times, SG successfully advocated for allowing students to self-assign pronouns in the Orion system. This initiative was led by River Bluhm, a senior Political Science major and SG Senator. Bluhm, who is also Vice President of Pride, listed Adam Richards among the reasons they became involved in student advocacy.

Bluhm started work on the pronoun selection project in early 2021, when they first took office as chair of SG’s Diversity and Equity Committee. Bluhm described their role in the project as “getting the ball rolling.” They reached out to the GGC, OIT, and SG’s Technology Committee to figure out the best way to implement the project.

“Really, everyone was pretty much on board,” Bluhm said. And yet, because of various bureaucratic issues, the project still took over a year to actually implement.

“The biggest issue I ran into was people from OIT didn’t want the ‘other’ option to open a text box where people could write whatever they want — and it wasn’t because they could write harmful things or anything,” Bluhm said. “It was because they wanted to be able to visualize the data better.”

This is the biggest problem with student-led advocacy. People want change, but even when administration is supportive, students typically aren’t prepared to wade through months of bureaucracy and minutia. And on top of that, the work never ends.

For example, allowing students and faculty to use a preferred name in the Orion system has been a years-long and ongoing issue. For many years, students could only change their display names in certain parts of the system, and could not use a preferred name on their Comet Card. Thanks to the efforts of many people, today students can easily change their display name by emailing records@utdallas.edu, but changing the names associated with one’s UTD email and Comet Card are still separate additional processes. Discussions about this are ongoing.

“It’s going to take a ton of time. Being an officer takes way more time than you’d think,” Richards warned.

In the end, that’s what killed Rainbow Guard. Pride and Rainbow Guard had a lot of overlapping membership, and according to Richards, “there just weren’t enough officers to go around.” Rainbow Guard ceased operations in 2018, and only a couple of years later, Pride also failed to meet the Student Organization Center’s minimum officer requirements.

But in 2021, a handful of students realized that there was no longer any large, general LGBTQ+ club, and started an effort to restart the organization. In 2022, Pride officers would be instrumental in organizing student response to the Farage scandal. Along with the other members of the Rainbow Coalition, an organization composed of leadership from UTD’s half-dozen LGBTQ+ clubs, they organized media releases, interviews, and events drawing attention to the issue.

Individual people can have a tremendous impact on a community. Even at the peak of Rainbow Guard’s activity around 2016, only about a dozen people regularly attended meetings. And yet, if not for this small group of students lobbying the administration in the mid-2010s, UTD might have been a much less inclusive place.

When asked to give advice to students looking to work in advocacy, Richards advised that advocacy groups consciously focus on training the next generation of leaders. They also emphasized the importance of having diverse leadership, especially trans people and people of color.

“Who has the opportunity to ascend to those heights is — not a perfect cipher, obviously — but it’s a good marker of where an institution is at, in terms of diversity and inclusion and being able to make that sort of difference,” Richards said.

“Having even one trans person in the room can change the entire conversation by bringing insights that would have gone unheard. And this can be applied to any marginalized identity,” they added.

The Supreme Court rulings of the past summer have left the nation in critical condition. When federal protections are overturned, decisions surrounding these rights are left to the states. As more power is allocated to states, the importance of local activism grows — and that includes student advocacy. It only takes a few dedicated people to make a change. Now more than ever, UTD needs students who are willing to stand up, and do the work.

content gathered by sebyul paik

Comments