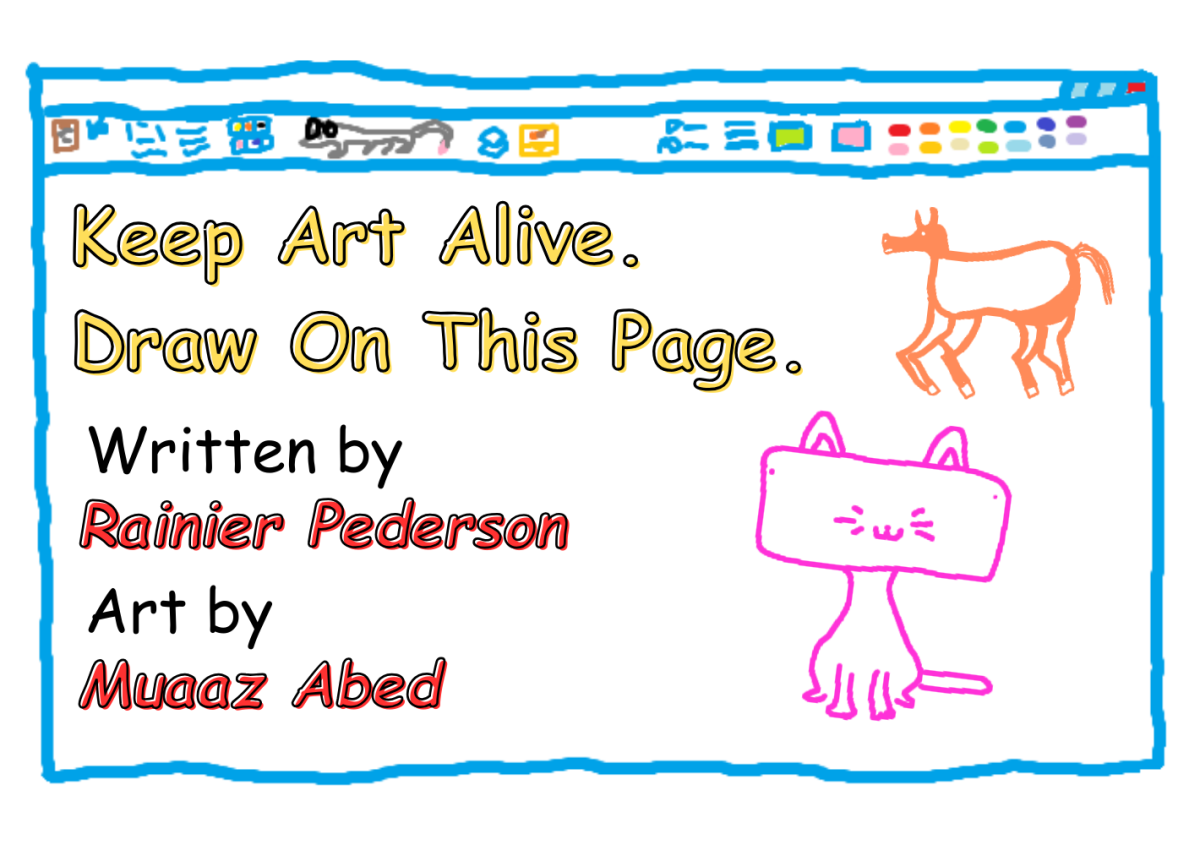

Imagine you’re a caveman. It’s been a long day, and you’re sitting down with your tribe to eat. Suddenly, an idea strikes. You take some melted animal fat, combine it with crushed charcoal, and take to the cave walls. In crude lines, you depict the last creature you hunted, the might of the beast captured in a raw sweeping gesture. Thin lines slowly come to form the legs and arms of your fellow hunters. Curves morph into bows, triangles into arrowheads. Someone adds their handprint to the wall, a testament to their existence. More hands join the wall. You are all there. You are alive. Archaeologists thousands of years from now will observe your spirit, still captured in those walls.

Congratulations. You have made art. If you want to repeat this experiment now it’ll probably be easier to grab a pen and paper, but the point stands. If you want to draw more than stick figures, it’s never been easier to learn — I have never met an artist who doesn’t owe at least some of their skill to free internet tutorials. Even if you don’t care to go out of your way to improve, even if you haven’t drawn since you were 10, even if you “can’t draw more than a stick figure,” you can be an artist. Right now. You can open Paint or your notes app and draw a cat right now. Do it.

But on a societal level, something here’s been lost in translation. When people think of art, they think first of the Mona Lisa or Starry Night. When most people think of artists, they think of Kahlo before they think of themselves. So when companies promise that generative AI can “democratize” art, a non-zero number of people buy it. They see the crimson rose held between fanged vampiric teeth and mistake the red of the petals for a warmth they forget they themselves emit.

The only thing AI-generated content is democratizing is the collective death of our souls.

When I say “content,” I mean “thing” as opposed to “art.” Content is something in the background — pretty shapes and colors. Art is something we choose to interrogate more, that we can be curious about. I don’t say this to be pretentious: when I worked as a waiter, I would read the fortune cookie fortunes people left on their plates and think about authorial intent while wiping down the table. Those fragile pieces of paper stained with sweet and sour sauce were just as much art as any Magritte. This piece may be art to you, or it may be content to someone else. If I do my job well, I might get more people to think it’s art, but that’s not entirely in my control nor inherent to these thousand or so words.

With that in mind, our lives are filled with objects that could really go either way — someone had to think about the UI of eLearning, the cut of your clothes, the shade of yellow on #2 pencils. It’s an interesting exercise to think about this, but at the same time, I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning if I spent all my time interrogating the pattern of my bedsheets.

But back to Starry Night. People have seen art hanging in museums, they’ve seen copies of famous works in their art classes, and they may have written about the technical prowess of one of their teachers’ top 20 favorite historical artists. Now, the art within museums is associated with some unknowable, elitist art world; famous works are associated with dead people, and even the art of the modern era (from animated TV shows to Instagram art posts) feels out-of-reach. Slowly, the term “art” loses its association with anything inherently human and fun — talking about “art” becomes a game of noticing when the shapes and colors look “art-y.” It becomes mere content.

In this context, I understand how people end up seduced by the fantastical promises of today’s technological Mephistopheles. I understand how a group in an introductory art class used AI because they were worried their final project wouldn’t look “professional” enough. I understand the essays prompted by insecure students or, for a more extreme example, the people using AI to help them respond to their loved ones’ texts.

But somewhere in that process, we lose a bit of ourselves. We lose the one thing that connects us to those handprints on the walls, painted thousands of years ago. We lose our unique voice, at best commissioning a software to think for us and at worst satisfied by an amalgamation of the internet’s data-turned-content. And in service of what? Conversations between two literally emotionally robotic parties? Words posing as information, conveying no thought? Pretty shapes and colors that can’t invite interrogation?

To this end, I think we could all get more comfortable creating bad art. Write technically “bad” fanfic and have fun doing it. Make some OCs and, in the grand tradition of many budding young artists, throw them into scenarios. Follow a Bob Ross tutorial with crayons or colored pencils and appreciate your influence on the paper. If you haven’t already, and I am serious when I say this, open Paint or your notes app and get to it. And if it looks like a caveman drew it, that’s what connects you to the rest of humanity.

![How the Women of INVINCIBLE are [TITLE CARD]](https://ampatutd.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/How-the-women-of-INVINCIBLE-are-TITLE-CARD-WEB-1200x845.png)